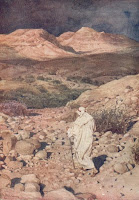

“And the Spirit immediately drove him out into the

wilderness” (Mark 1:12)

Lately I am not into wilderness. I don’t want to be in a

place, physical or metaphorical, where I am at the mercy of the elements, where

I am unsafe, where my very survival is at issue. I much prefer to be in control

of my surroundings, feel safe in the life I have ordered, and have my mind on

things higher up on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs than simply staying alive.

Therapeutic moral deism—a popular distortion of Christianity which envisions a

God whose sole purposes are to improve my life and help me follow clearly

demarcated moral guidelines—encourages me, perhaps unintentionally, to avoid

the wilderness. But here in the gospels, Jesus is led (driven!) by the Spirit

into the wilderness. And here in Lent, if I am to enter into this season of

reflection, I am invited to reflect on the reality of wilderness. And I am

beginning to think that, in many ways, I am in the wilderness like it or not, so

I might as well face it.

The biblical scholar in me is helpful at this point. I can

take a step back from my personal feelings about entering the wilderness and

ask what wilderness meant to the gospel writers, when they chose to include

this detail from the life of Jesus in their narratives. Recognizing the

cultural, historical, and literary context of this event from the life of Jesus

is a good starting point. Such reflection can provide some guidance for more

personal reflections about wilderness.

|

| source: faith.nd.edu |

For Jewish writers in the first century, the wilderness could

be viewed as a place of individual isolation and struggle, but that was not its

only meaning. The theme of “wilderness” also had many other connections, some

with deep roots in the Jewish worldview embraced by the New Testament writers. Wilderness

was the place where their ancestors had wandered for forty years: a place of communal

(rather than individual) purification and testing. It was also a place of a

place of divine revelation. Moses is associated with the wilderness,

encountering God at the burning bush and receiving the Torah on Mt. Sinai, in

addition to leading the Israelites through their wilderness wanderings. All of

these aspects of Israelite history suggest the importance of wilderness for the

early Jewish worldview. In addition, in the period of the Second Temple, the

wilderness was a place where rebel leaders against oppressive regimes had

gathered their forces, particularly in the Maccabean era. Finally, the

wilderness has associations with the concept of exile: the forced removal of

the people of Israel from the land of promise during the era of the monarchy.

Though the Bible also recounts a return from exile in the era of king Cyrus,

for many Jewish authors in the Second Temple period, the exile continued to

define their reality as separated in some way from the covenant blessings of

God.

With this rich palate of associations related to the idea of

“wilderness,” any serious reader of the New Testament might want to pause to

consider what particular connotations may be in mind when a gospel writer explicitly

points out that Jesus was led into the wilderness. One might expect divine

encounters and divine revelation in a narrative that involves a journey into

the wilderness. (For an accessible and helpful look at the significance of the wilderness

in the era of the New Testament, see Daniel Smith’s Into the World of the New Testament, especially chapter four).

To me, it seems that the notion of the wilderness in these

passages makes a link between Jesus and Moses very strong. Such a connection is

supported when we see other places in the gospels where Jesus and Moses are

both shown to be a part of God’s working in the world (see John 1:17, for

example). The full significance of Jesus can only be appreciated when his

advent is seen as part of the long history of God’s working in the world. For

the earliest Christians, themselves Jews, the significance of Moses and the

Torah cannot be overestimated. Thus, in his being led into the wilderness,

Jesus is shown to be a participant in God’s age old plan of redemption of God’s

people. And this to me is a vital recognition: for the gospel writers Jesus is

not just a radical new initiative on the part of God to redeem humanity. Jesus

is part of God’s plans from of old. “Wilderness,” as a theme, is one way of

showing that connection to the reader.

This way of reading the wilderness temptation of Jesus does

not preclude the idea that Jesus models a personal practice of piety in which

one is purified through time alone in the wilderness, even as one faces and

strives to resist temptation. Christians have always identified personally with

this narrative, finding in it encouragement and hope when in temptation. But it

is important to also recall that a personal application of this passage to “my

life” is not the whole story. Jesus’s going into the wilderness is a way of the

gospel writer saying: “Hey, pay attention. This story I am recounting is not only

about a unique individual overcoming temptation; what follows will be rich with divine

revelation.” Just as God was revealed in the wilderness in the past, God is

being revealed in the gospel in the life of Jesus, albeit in a new way. The gospel writers are

inviting us to make the connection that this

story (the story of Jesus) is part of that

story (the story of God and God’s people). New Testament historian N. T. Wright

puts it this way: “Jesus is acting out the great drama of Israel’s exodus from

Egypt, Israel’s journey through the wilderness into the promised land” (Mark

for Everyone, p. 6).

When I think about this passage, yes it can lead me to think

about my own experience of wilderness, my own experience of exile. I can take

comfort in knowing that Jesus was in the wilderness as well, and that I am not

alone in whatever physical or spiritual wilderness I find myself. Those are

good things to consider. But I can also consider the larger idea that the story

of Jesus is a part of the ancient story of God’s redemptive work in the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment