In honor of Black History Month here is a reflection that I read at a university leadership meeting on MLK day a few years ago. In it I draw attention to a figure you may not be familiar with. You may know something of Howard Thurman, but I knew very little until doing research for my book on the parables and social justice. Thurman was an author, preacher, philosopher, theologian, and civil rights leader. He held academic posts as dean of the chapel at Howard University and Boston University, and also founded an interdenominational church in San Francisco. He has been called “a spiritual genius who transformed persons who transformed history” (Smith, xi). His particular relevance today is that he was a mentor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. It was reported that Dr. King always carried a copy of Thurman’s book, Jesus and the Disinherited, whenever he traveled. John Lewis and the freedom riders also circulated Thurman’s writings to encourage one another. In reading Thurman, it is really interesting to see the insights behind some of Dr. King’s powerful statements. As a leader at a Sisters of Mercy university, it is interesting too to see links with the teachings of the Sisters of Mercy.

Here I share five insights from Thurman and make some linkages to Dr. King, and to our work today at a Catholic, Mercy university.

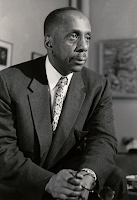

|

| Source: Howard Thurman: The Overlooked Civil Rights Hero |

Second, for Thurman, this leads to a goal in human life of freedom to self actualize. To grow, to live, to live fully out of the center of who one is. A quote of Thurman’s you may have heard is this one: “Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.”

Third, recognizing this inherent value for oneself, one must also recognize this reality for others. And with this recognition comes a twofold threefold obligation: to work toward community (love); to support the freedom to live and grow for others (mercy); and to work against forces of oppression and dehumanization (justice). Ultimately, this amounts to working toward a community in which all may thrive; what Martin Luther King, Jr., called the “beloved community.”

Fourth, this activity is supported by the recognition of the inter-connectedness of all of life—humans and creation, because all of it is God’s creation, created out of love. So genuine religion, and in particular genuine Christian faith, aligns with love and fosters a sense of obligation for the well-being of all in the present world, regardless of its apparent brokenness.

Fifth, for Thurman, Jesus was the ultimate example of this, as well as the ultimate teacher. Coming into the world and living, teaching, and dying with the Jewish people under the domination of the Roman Empire, among the oppressed, his was a message for the disinherited. That they could live effectively in that chaos with the recognition that they were children of God. The kingdom of God that Jesus proclaimed could be defined broadly as the conceptual space in this world where God’s highest values are enacted in human lives. Put more simply, the kingdom of God is the enactment of and participation in loving community.

With those five points as background, I would like to return to one of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, quotes that has resonated with me in recent years. The quote is from his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, April 16, 1963. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” There is a lot of Howard Thurman behind this. In addition, King’s concept of the beloved community is one that is undergirded by Thurman’s insights on the value of all people, and the critical importance of working toward a community which supports all its members, and in which each person is free to thrive.

Having worked at a Sisters of Mercy university for ten years, it is so interesting to see that these statements connect at a deep level with the Sisters of Mercy concept of a more just and merciful world. They also resonate with Catholic Social Teaching and in particular the theological virtue of solidarity—a virtue which is much needed in our present, fractured world.

Bryan Massingale is a contemporary scholar who writes on racial justice and the Catholic Church and also points to the importance of solidarity. He cites Pope John Paul II who defined solidarity as a “firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all” (116). Massingale also used King’s words to explain that “solidarity is based on the deep-seated conviction that the concerns of the despised other are intimately bound up with our own, that we are, in the words of Martin Luther King Jr., ‘bound together in a garment of mutual destiny’” (116). Massingale also notes, “Solidarity entails a constant effort to build a human community where every social group participates equitably in social life and contributes its genius for the good of all” (117). These words inspire a powerful vision for the kind of world we all would like to live in.

As we wrap up our celebration of Black History Month may we all remember the legacy of leaders who have come before us, may we acknowledge the work still to be done in the struggle against the evil of racism, and may we make every effort to live into the best aspects of the rich heritage which we have each been given as we face the challenges of this moment.